Why teachers stop teaching - part 2

A few days ago, I got in my first ever Twitter scuffle (I won't call it an all-out Twitter war, because let's be honest, I'm not that important) with a local journalist. He wrote about the contract dispute between the teachers and the local school district, blaming teachers and labor unions for the school district's budgetary problems. I disagreed. A lot. I also felt the facts he used in his article were misleading, and in some places outright incorrect. So I responded to him directly and wrote a fairly lengthy blog post airing my opinion.

If you haven't read the first part of this post, it's fairly lengthy. In short, I talk about how teachers are educated professionals that deserve to be treated with respect and deserve to be paid a reasonable salary. Eventually, teachers leave the profession for lack of money.

I shared it on social media and got quite a bit of feedback - much more than usual. I was very fortunate, as most comments that I saw were positive -- and I'll be honest, I didn't see all of them. The post was shared a number of times, so I'm not sure exactly where it ended up. And I felt some of it was truly worthy of exploring.

Some teachers and former teachers wanted to clarify that they didn't leave (or consider leaving) because of financial reasons. Their issues were with professionalism and unrealistic expectations.

In my mind, this was two sides of the same coin. In my mind, salary is a tangible measure of how much one is valued in their chosen profession. But, some did not see it that way.

If you, dear reader, have never been a teacher -- it is an exhausting, and often thankless career. We've all seen the movies and read the stories, and talked to friends-of-friends who teach, but nothing compares to the daily grind of the life of a classroom teacher in 21st century America.

My husband still teaches full time, here is his daily schedule:

5:30 - alarm goes off

6:10 - leave the house

6:30-7:00 - before school "prep time"

7:00 - 2:00 - school. I'll be very honest, I don't know his exact schedule this year.

About 3:00* - arrive home

*Exception on Wednesdays when there is mandatory training for 1 hour after school

8:30 - bed

So -- not so bad, right? Except, between 3pm and 8pm, he probably spends 2-3 hours every night doing something school related. He grades papers, he researches and writes new lesson plans, he reads books that he's planning to teach. Literally right now, he's sitting next to me writing a worksheet for his class.

He also works about 20 weekend hours per month lesson planning and inputting grades.

This isn't counting football games, social events, plays, or other extra-curricular events that we might go to outside of regular school hours. He doesn't have to go to those things, but students, parents, and administrators like to see teacher faces there.

So in addition to his regular 40 hour week, he works about 10 "overtime" hours per week at home, and an average of 5 more hours per week on the weekend. Conservatively, he's up to 55 hours per week. I know many teachers that can easily log 60-70 per week with coaching or club duties.

I typically log about 50 hours per week. But, I have a comfortable desk chair, free access to coffee and restrooms, and a daily, hour-long, lunch break that I can take whenever I get hungry. I am treated like a professional. As long as I get my work done, and do it correctly, I will have the freedom to do what I need to do on my own timeline. I work largely by myself with some daily contact with my supervisors. I take an occasional phone call.

Teaching is not like that. It is a daily marathon of phone calls, emails, parent concerns, administrators, and students. If you're lucky, you get 20 minutes for lunch - which includes bathroom time. You're on your feet all day and constantly fielding questions. Also, you have to teach stuff. It's exhausting on a good day. On a bad day, it is soul crushing.

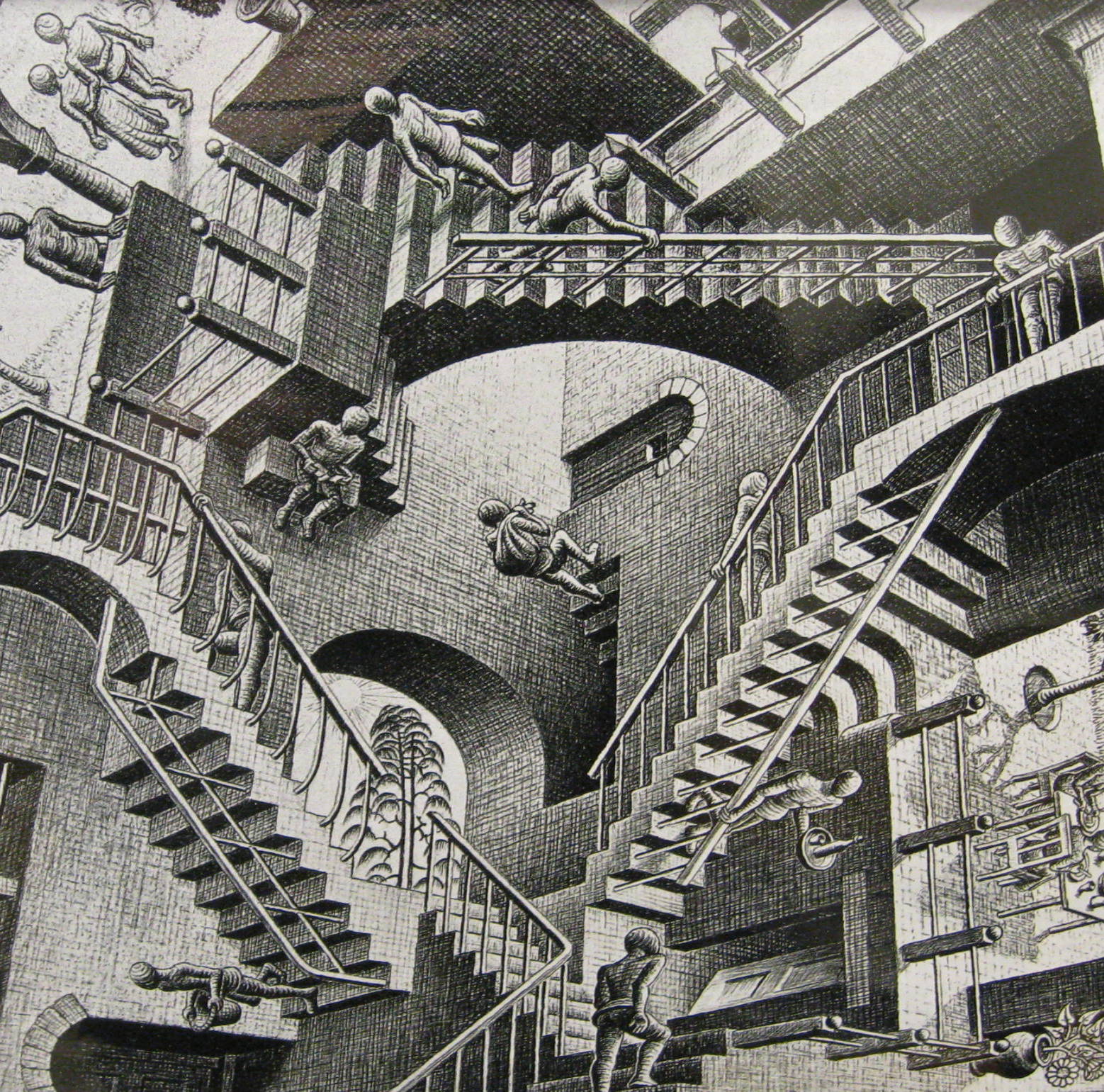

That was the part that some of the online commenters pointed out that I missed. The soul-crushing part of teaching. I'm not going to lie. Yeah. Part of me LOVED teaching with ever fiber of my being, but another part of me felt like I was forever trying to run up the "down" escalator.

No matter how hard I tried, I could never get ahead. There was always something else to do. Any time I thought I had checked everything off my list, I got a new list. There were simply not enough hours in the day to grade all of the papers, enter all of the grades, attend all of the meetings, call all of the parents, and write lesson plans. If I did everything I was asked to do and didn't cut any corners, I would easily spend 70 hours per week working.

And in the end, I was cutting all of the corners. I would half-write lesson plans, I would sort-of grade assignments. I was still teaching my classes and giving my students all of the attention they craved, which felt like the most important part, but I kind of let the rest of it slide. Every once in a while I would panic and realize I could get fired if I didn't do those other things and I'd try to catch up, but it was a viscous cycle. A couple of times I got "the talk" about how I was falling down in my duties as a teacher.

And I'm not alone. In addition to teaching, teachers today are required to: write and post daily lesson plans for each class they are teaching (some teachers may teach 4-5 classes), grade student assignments and input multiple grades for each student every week, work with colleagues to develop long-term curriculum, attend IEP and 504 meetings for students with special needs, attend school-wide training sessions and subject-specific training sessions as needed, and maintain open lines of communication with parents, just to list a few. Some schools require teachers to maintain class webpages where they post daily assignments or weekly schedules. Teachers also organize fundraisers for their classrooms, volunteer as coaches and activity advisors, and work on school-wide committees. One year I mentored a new teacher. I think I scared her off.

In the end -- as much as I loved teaching, and as much as I loved my students, it just couldn't make up for the soul-crushing nature of the rat-race teaching had become. I realized that I wasn't even spending that much time with my students anymore. In an average week, I was spending about 30% of my work hours teaching students. The rest of the time was spent grading, planning, meeting, etc.

Even when I could teach, it wasn't about teaching - it was about "assessment." How could I prove, on paper, that my students learned something from me that day? I had to find some objective way to measure what was going on inside the brains of 100 kids every day. When I was lucky, I got to make up the assessments. The rest of the time they are random state-funded assessments that no one can ever predict. We spend all of our time teaching kids "test-taking strategies" so they can do well even when the questions are insane.

To look at that another way, I was mostly a bureaucrat that occasionally got to teach students. That's the part that wears on teachers. When you first start, you tell yourself "well, it's like this because I'm new. Once I know what's going on, it will all be ok!" A few years in you kind of hit your stride, but then something happens - a new textbook, new regulations, new lesson planning guidelines - something. Then you start over from scratch. There's no time to learn the new thing. You're just told to "roll with it."

The last few years were the most stressful. Every year, I was expected to do more with less. There was no money in the budget, no supplies, and no hope of getting anything. But, I still had to have a fully stocked and functioning classroom with multi-media components (that would be part of my professional evaluation), and engaging lessons. People were constantly evaluating the effectiveness of my classroom by coming in ten minutes at a time to observe me with my students. After 10 minutes, they would leave me with advice on how to make my classroom better. And then a few weeks later they would come back, unannounced, to see if I'd implemented their advice.

Now lets put all of this together...

OMG! Kermit is using the wrong your/you're!

If you haven't read the first part of this post, it's fairly lengthy. In short, I talk about how teachers are educated professionals that deserve to be treated with respect and deserve to be paid a reasonable salary. Eventually, teachers leave the profession for lack of money.

I shared it on social media and got quite a bit of feedback - much more than usual. I was very fortunate, as most comments that I saw were positive -- and I'll be honest, I didn't see all of them. The post was shared a number of times, so I'm not sure exactly where it ended up. And I felt some of it was truly worthy of exploring.

Some teachers and former teachers wanted to clarify that they didn't leave (or consider leaving) because of financial reasons. Their issues were with professionalism and unrealistic expectations.

In my mind, this was two sides of the same coin. In my mind, salary is a tangible measure of how much one is valued in their chosen profession. But, some did not see it that way.

If you, dear reader, have never been a teacher -- it is an exhausting, and often thankless career. We've all seen the movies and read the stories, and talked to friends-of-friends who teach, but nothing compares to the daily grind of the life of a classroom teacher in 21st century America.

5:30 - alarm goes off

6:10 - leave the house

6:30-7:00 - before school "prep time"

7:00 - 2:00 - school. I'll be very honest, I don't know his exact schedule this year.

About 3:00* - arrive home

*Exception on Wednesdays when there is mandatory training for 1 hour after school

8:30 - bed

So -- not so bad, right? Except, between 3pm and 8pm, he probably spends 2-3 hours every night doing something school related. He grades papers, he researches and writes new lesson plans, he reads books that he's planning to teach. Literally right now, he's sitting next to me writing a worksheet for his class.

He also works about 20 weekend hours per month lesson planning and inputting grades.

This isn't counting football games, social events, plays, or other extra-curricular events that we might go to outside of regular school hours. He doesn't have to go to those things, but students, parents, and administrators like to see teacher faces there.

So in addition to his regular 40 hour week, he works about 10 "overtime" hours per week at home, and an average of 5 more hours per week on the weekend. Conservatively, he's up to 55 hours per week. I know many teachers that can easily log 60-70 per week with coaching or club duties.

I typically log about 50 hours per week. But, I have a comfortable desk chair, free access to coffee and restrooms, and a daily, hour-long, lunch break that I can take whenever I get hungry. I am treated like a professional. As long as I get my work done, and do it correctly, I will have the freedom to do what I need to do on my own timeline. I work largely by myself with some daily contact with my supervisors. I take an occasional phone call.

Teaching is not like that. It is a daily marathon of phone calls, emails, parent concerns, administrators, and students. If you're lucky, you get 20 minutes for lunch - which includes bathroom time. You're on your feet all day and constantly fielding questions. Also, you have to teach stuff. It's exhausting on a good day. On a bad day, it is soul crushing.

That was the part that some of the online commenters pointed out that I missed. The soul-crushing part of teaching. I'm not going to lie. Yeah. Part of me LOVED teaching with ever fiber of my being, but another part of me felt like I was forever trying to run up the "down" escalator.

No matter how hard I tried, I could never get ahead. There was always something else to do. Any time I thought I had checked everything off my list, I got a new list. There were simply not enough hours in the day to grade all of the papers, enter all of the grades, attend all of the meetings, call all of the parents, and write lesson plans. If I did everything I was asked to do and didn't cut any corners, I would easily spend 70 hours per week working.

And in the end, I was cutting all of the corners. I would half-write lesson plans, I would sort-of grade assignments. I was still teaching my classes and giving my students all of the attention they craved, which felt like the most important part, but I kind of let the rest of it slide. Every once in a while I would panic and realize I could get fired if I didn't do those other things and I'd try to catch up, but it was a viscous cycle. A couple of times I got "the talk" about how I was falling down in my duties as a teacher.

And I'm not alone. In addition to teaching, teachers today are required to: write and post daily lesson plans for each class they are teaching (some teachers may teach 4-5 classes), grade student assignments and input multiple grades for each student every week, work with colleagues to develop long-term curriculum, attend IEP and 504 meetings for students with special needs, attend school-wide training sessions and subject-specific training sessions as needed, and maintain open lines of communication with parents, just to list a few. Some schools require teachers to maintain class webpages where they post daily assignments or weekly schedules. Teachers also organize fundraisers for their classrooms, volunteer as coaches and activity advisors, and work on school-wide committees. One year I mentored a new teacher. I think I scared her off.

In the end -- as much as I loved teaching, and as much as I loved my students, it just couldn't make up for the soul-crushing nature of the rat-race teaching had become. I realized that I wasn't even spending that much time with my students anymore. In an average week, I was spending about 30% of my work hours teaching students. The rest of the time was spent grading, planning, meeting, etc.

Even when I could teach, it wasn't about teaching - it was about "assessment." How could I prove, on paper, that my students learned something from me that day? I had to find some objective way to measure what was going on inside the brains of 100 kids every day. When I was lucky, I got to make up the assessments. The rest of the time they are random state-funded assessments that no one can ever predict. We spend all of our time teaching kids "test-taking strategies" so they can do well even when the questions are insane.

To look at that another way, I was mostly a bureaucrat that occasionally got to teach students. That's the part that wears on teachers. When you first start, you tell yourself "well, it's like this because I'm new. Once I know what's going on, it will all be ok!" A few years in you kind of hit your stride, but then something happens - a new textbook, new regulations, new lesson planning guidelines - something. Then you start over from scratch. There's no time to learn the new thing. You're just told to "roll with it."

The last few years were the most stressful. Every year, I was expected to do more with less. There was no money in the budget, no supplies, and no hope of getting anything. But, I still had to have a fully stocked and functioning classroom with multi-media components (that would be part of my professional evaluation), and engaging lessons. People were constantly evaluating the effectiveness of my classroom by coming in ten minutes at a time to observe me with my students. After 10 minutes, they would leave me with advice on how to make my classroom better. And then a few weeks later they would come back, unannounced, to see if I'd implemented their advice.

Now lets put all of this together...

- the long hours

- the never-ending tasks

- the assessments

- the bureaucracy

- the unattainable expectations

- the unsolicited advice

Do you want that job?

How about if you have to go to 5 years of college, spend thousands of dollars on licensing, and get paid a handsome salary of $40,000.00 per year?

Oh! AND you get demonized in the media for being "greedy" in your salary demands.

Yeah, probably not.

I didn't either. So that is why I, and millions like me, stopped teaching. It's not because I wasn't good at it. It's not because I didn't love my students (see my crying llama posts from last October). It's not because I "couldn't cut it." It was because on balance, I valued myself more than the school district did and chose to move into a profession that agreed with me.

Comments

Post a Comment